The rich histories of ancient Native American peoples who lived in the Four Corners region are preserved at countless sites today.

By Josephine Matyas, F468364

March/April 2025

Four Corners — the area where the Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona borders meet — is a dry, windswept landscape of mountains, red-rock mesas, buttes, high desert, and gaping canyons created over millions of years.

To the descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans, the ancient civilization that ruled this region for thousands of years, the land is sacred and inseparable from their culture.

Dancers at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque demonstrate Native American traditions.

Blacktop and washboard roads lead to communities that preserve the history of these villages, or pueblos. Each has a unique story to share of the migrations, the growth, and the once flourishing communities.

The area holds numerous ruins and vibrant stops ideal for an RV road trip. Begin at the not-for-profit Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Owned and operated by the 19 Pueblos of New Mexico, it’s devoted to the history, culture, traditions, and accomplishments of the Pueblo peoples.

Here are a few “must see” spots —although many others are close by. Please respect the etiquette rules at all these sacred sites. Also, note that some sites are best explored with a towed/towing vehicle. Check the National Park Service websites and other online info prior to your visit.

NAVAJO NATIONAL MONUMENT, ARIZONA

Many native peoples trace their ancestry to the ruins of Bétatakin (“house on a ledge”), protected at Navajo National Monument. The visitor center’s small museum displays artifacts of pottery and tools from the cliff dwellings of Ancestral Puebloans in Tsegi Canyon.

It’s an easy hike to the rock overlook at the Bétatakin ruins. With 135 rooms, Bétatakin was home to up to 100 people, who farmed corn, squash, and beans, and created ceramics and textiles. Around the late 13th century, the people left Tsegi Canyon and headed south to new settlements — archaeologists speculate that drought, erosion of farmable lands, or conflict with neighbors may have driven them to abandon their cliff homes. The park also preserves remains of the Keet Seel and Inscription House cliff dwellings.

Getting there: The best route to the park is from U.S. 160, then north on Arizona Route 564 (northeast of Tuba City and southeast of Page). Cell service is not a sure thing.

Camping: Free dry camping is available in the park at Sunset View and Canyon View campgrounds. Sites can accommodate RVs up to 28 feet and are available on a first-come, first-served basis. Access may be difficult for larger RVs, especially at Canyon View Campground, because of narrow, unpaved gravel roads and low-hanging branches.

HOVENWEEP NATIONAL MONUMENT, UTAH/COLORADO

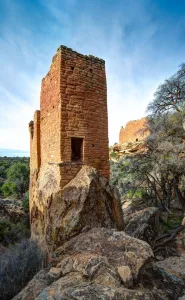

This ancient tower, part of the Holly Group at Hovenweep National Monument, stands in Keeley Canyon.

The Ancestral Puebloans of Hovenweep lived in vibrant communities in clusters of buildings along Little Ruin Canyon, mostly from AD 1200 to 1300. They were efficient dry farmers also known for their distinctive black-on-white pottery and turquoise crafts. Today the site protects rock, wood, and mud mortar towers found along a level hiking trail from the visitor center.

Eight centuries ago, the Square Tower community was part of a sizable network of Ancestral Puebloan prehistoric villages across the region. The residents were resourceful, incorporating terraced gardens into the canyon slopes, creating dams along the river to collect water, domesticating dogs and turkeys, and using dry-land farming techniques to raise crops like maize and squash.

Like other Four Corners Ancestral Puebloans, they abandoned their tower community in the 13th century. Exactly why is a matter of speculation, although their descendants are found in the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico and in Arizona’s Little Colorado River Basin. Today’s Zuni and Hopi people are descendants of the master builders of Hovenweep.

Getting there: Hovenweep is located along the border between southeast Utah and southwest Colorado, about a one-hour drive from either Blanding, Utah, or Cortez, Colorado.

Camping: The park campground has 31 sites, although not all can accommodate RVs (maximum length 36 feet). Flush toilets are available but no hookups, showers, or dump station.

MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK,COLORADO

Mesa Verde was the first U.S. national park established to protect human-made structures rather than natural features alone, safeguarding 5,000 archaeological sites. It also is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site and International Dark Sky Park.

Today, Mesa Verde National Park protects the cultural heritage of 27 pueblos and tribes.

It takes 45 minutes to drive from the visitor center at the base to the popular Mesa Top (much of it a steep, winding route). Once on top, add time for stops to peer into circular kivas — the subterranean religious chambers — as well as pithouses from the early Basketmaker period, and above-ground buildings made of “wattle and daub” masonry.

The wow factor peaks at Cliff Palace, the most impressive of the park’s 600 cliff dwellings, with 150 rooms. The Ancestral Puebloan people lived, worked, and raised families under these rock overhangs. (At this writing, the Cliff Palace Loop Road is closed for construction. However, the park’s website notes the site can be seen from Sun Temple, on the Mesa Top Loop.)

Ranger-led tours follow a narrow trail into the ruins. Without the benefit of the wheel or the horse, it must have taken many years to build these structures. By the year AD 1300, Mesa Verde was deserted; the exact reasons are unknown. The people moved, and their descendants are found in the Zuni and Laguna pueblos, other pueblos along the Rio Grande, and on Hopi lands in the middle of Arizona’s Four Corners. Many of the native cultures that thrive today trace their ancestry to the ancient builders at Mesa Verde.

Getting there: Mesa Verde is in the southwest corner of Colorado, between the towns of Mancos and Cortez on Highway 160.

Camping: Morefield Campground is managed by park concessioner Aramark and open spring to fall. It includes 267 campsites (15 with hookups), although many are not level. Showers and a dump station are available nearby.

ACOMA PUEBLO/SKY CITY, NEW MEXICO

On top of a barren, windswept butte — sometimes described as a 70-acre island 30 stories above the desert floor — sits the New Mexico pueblo known as Acoma, or Sky City. Established around AD 1100, it is said to be the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America.

Many homes atop the mesa at Acoma Pueblo — also called Sky City — have ladders with which to access the upper floors.

The Acoma legend tells of sacred twins who led their ancestors to Haak’u (meaning “a place prepared”) at the top of the sandstone mesa. The brothers showed the Acoma people the finest clay in the region, giving birth to a long tradition of master potters who create prized, thin-walled vessels of white clay decorated with black geometric lines.

Until the late 1950s, the only way up to Acoma was to climb a rough foot-hole trail that zigzagged back and forth through slices in the steep rock walls. The Spanish conquistadors — intimidated by the defensive nature of Acoma when they viewed the site in 1540 — immediately declared the settlement on the bluff as “a rock with a village on top, the strongest position in all the land.” That didn’t deter them from storming Acoma and inflicting years of injustice, slavery, and brutality on its inhabitants.

Centuries later, terrain was bulldozed to create a narrow road that served as the settlement’s main link to the pristine valley and desert below. Before the days of road travel, generations of the Acoma people hauled tons of earth and rock up the narrow pathway to construct the 300 village buildings out of adobe brick and white sandstone blocks. Among the structures created was San Estevan del Rey Mission, now a National Historic Landmark. A few families live atop the mesa full-time, and many tribe members still own homes in the multistory adobe buildings that line the uneven, dirt pathways of Sky City.

Access to the pueblo is strictly controlled, to respect and maintain the vibrant spiritual home of the people of Acoma. Visitors can take a guided walking tour of the village.

The Haak’u Museum in the Sky City Cultural Center protects a millennium of Acoma history, artifacts, ancestral remains, and teachings. The stacked stonework and the T-shaped doorways pay homage to the tribe’s migration history from Chaco Canyon.

Getting there: Acoma Sky City is a 65-mile drive west of Albuquerque via Interstate 40 west to exit 102.

Camping: Sky City RV Park has 42 pull-through sites suitable for big rigs, along with full hookups, a dump station, and Wi-Fi.

BANDELIER NATIONAL MONUMENT, NEW MEXICO

The human presence engraved in the landscape at Bandelier National Monument is what the National Park Service calls “an open book of human history.” The Ancestral Pueblo peoples inhabited Bandelier from approximately 1150 to 1550 BC. Their culture was shaped by their life on the land, through changes at different elevations that provided them with food, medicine, and clothing.

At Bandelier National Monument, in the Talus House area, this view from a cavate (cliff dwelling) overlooks Frijoles Canyon.

Millions of years ago, a slumbering volcano erupted, spewing ash over an enormous area, which eventually hardened into talus. Then, wind and erosion created a maze of rugged canyons with tall cliffs — a sheltered location perfect for the longhouses, kivas, and cliff dwellings built by the people.

The standing masonry walls of the ruins are an easy walk from the visitor center along the Pueblo Loop Trail through Frijoles Canyon. It’s well worth the climb (on short ladders) to enter shelters built beneath the cliff overhangs, and to view petroglyphs carved into canyon walls.

The visitor center features pottery; clothing; instruments; and the oral traditions of song, dance, and storytelling still practiced by the Pueblo people of Tewa, Zuni, Cochiti, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, and Santa Clara, who have ties to Bandelier.

Getting there: Bandelier is a half-hour drive from Los Alamos, once home to the secret Manhattan Project laboratory. The spectacular Taos Pueblo is not far to the north.

Camping: Just inside the main park entrance, Juniper Family Campground has 53 sites in a beautiful setting. There are restrooms and a dump station but no hookups or showers.

CHACO CULTURE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK, NEW MEXICO

Once the ceremonial, trade, and cultural center of a great civilization that stretched across much of this area, Chaco Canyon is an excellent spot to ponder one of the great archaeological mysteries of the continent. In the 13th century, why did the Chacoans mysteriously disperse from this cultural and ceremonial hub, eventually settling and establishing the state’s 19 very distinct pueblos?

Chaco Canyon, once the center of Chacoan culture, spawned the construction of “Great Houses,” such as Pueblo Bonito.

But “gone” does not mean “disappeared,” because the modern Puebloan tribes, including the Hopi, Acoma, Zuni, and Laguna, trace their roots to the great houses of Chaco Canyon.

Archaeologists as well as archaeo-astronomers celebrate the hyper-organized ceremonial center of the Ancestral Puebloans at Chaco, creating an even deeper significance for the modern-day tribes.

Because of its remote location, this UNESCO World Heritage Site receives few visitors. Spread out across the canyon’s wild beauty of rock, piñon, and creosote, the excavated ruins are dominated by monumental architecture built with an estimated 50 million sandstone slabs. Multistory buildings with hundreds of rooms called Great Houses were oriented to solar, lunar, and cardinal directions. How the Chacoan people managed such sophisticated calculations is one of the great mysteries.

Life was organized around the harvest of corn, squash, and beans; thus, the ancients attuned their lives to seasonal patterns as the sun cut across their astronomical marker stones. So precise was this ancient calendar that they aligned the massive walls of Pueblo Bonito along the axis of the summer-winter equinox and then oriented distant buildings and roads to the same coordinates in an impressive feat of engineering.

Getting there: From U.S. 550, head south on County Road 7900, but don’t travel if the roads are wet.

Camping: Gallo Campground, located within the park, is open year-round and offers 24 sites for RVs under 35 feet. Water and restrooms with flush toilets are available but no showers or hookups. No fuel stations, auto repair facilities, food, firewood, or ice are available in the park . . . but enjoy the darkest skies you’ll ever see.

FOUR CORNERS INFO

When To Go

The Four Corners is high desert — hot in summer and cooler in winter (including some snow). Spring and fall are the best times to visit.

Navigating

AAA publishes an excellent detailed road map called Indian Country, available in many local shops.

Visit Arizona

visitarizona.com