It’s wise to familiarize yourself with possible solutions to the many issues that affect motorhome handling and drivability.

By Mark Quasius, F333630

July 2019

When a motorhome handles well, it can be a joy to drive. On the other hand, you may dread getting behind the wheel of a coach that handles poorly. Handling can be affected by parts that are worn or out of adjustment. Sometimes, handling can be improved by adding a component from a third-party supplier. But before you spend your hard-earned money, take time to learn a bit about your chassis and how things work.

Suspension Types

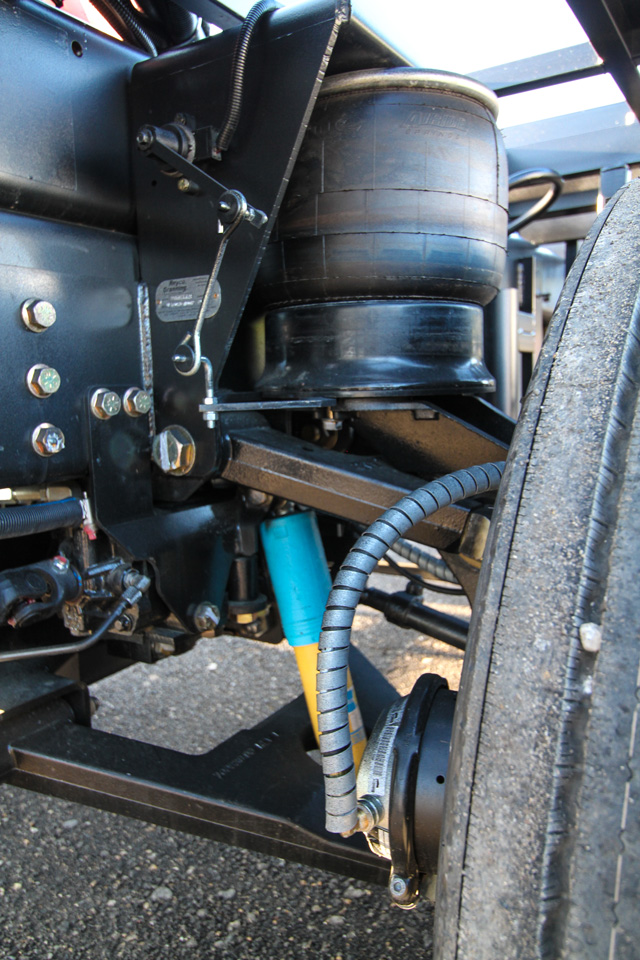

SumoSprings, which are designed to stabilize sway and improve driver control, are mounted next to leaf springs on this motorhome.

A motorhome’s chassis has a suspension system, which includes a steering subsystem. The four basic types of suspensions are leaf spring, coil spring, air spring, and torsion bar, although LiquidSpring’s CLASS (Compressible Liquid Adaptive Suspension System) is becoming more popular in RVs.

Today, most Type A gasoline-powered motorhomes utilize leaf-spring suspensions with solid I-beam-style front axles, while Type C coaches generally are equipped with independent front suspensions that utilize coil springs. The vast majority of diesel-pusher motorhomes have air-ride suspensions that use air springs, commonly referred to as air bags.

Leaf springs have been around since the Conestoga wagon days. The simple design provides weight-carrying capacity and locates the axle, holding it in place and preventing it from moving forward or backward beneath the vehicle’s frame. A leaf-spring bushing is fitted to the end of the leaf spring; a bolt through the bushing secures the spring to the spring shackle mounts.

Coil springs mount either above an axle or between a pair of control arms. Coil springs have no lateral control ability, so a stabilizing device is required. On an independent front suspension, control arms that contain the coil spring are mounted to the frame and prevent the wheel from moving forward or backward. If the coil spring is located over a solid axle, such as the rear drive axle, a series of control links holds the axle in place.

Air springs are similar to coil springs, except an air bag is used instead of a steel coil. The coach’s on-board air system pressurizes the air bag, and the amount of air is regulated by ride-height valves, which keep the coach riding at the correct height regardless of load conditions. As with coil springs, a series of control arms or links keeps the axle in place.

Today, torsion bar springs are not common on motorhomes, but they are popular on travel trailers.

First Checks

When a motorhome handles poorly, first check the tire pressure. Readings should be taken when tires are cold, not after they have been driven or warmed by sunlight. Stamped on every tire’s sidewall is an inflation pressure associated with the tire’s maximum load capacity. Unless you load the tire with the maximum weight, it won’t be necessary to inflate to the max pressure.

To determine the proper inflation pressures, weigh your coach when fully loaded and obtain four-corner scale readings. Compare those readings with the tire manufacturer’s inflation pressure tables (published on tire manufacturers’ websites) to determine the minimum inflation pressure needed to support the measured load.

Four-corner weighing is available at FMCA conventions. The Recreation Vehicle Safety and Education Foundation’s weighing schedule and locations are listed on its website (https://rvsafety.com). The FMCA Forums include a discussion on this topic: https://community.fmca.com/topic/716-where-can-i-get-individual-wheels-weighed/.

Diesel pushers with air-ride suspension are equipped with automatic ride-height valves. A mechanical arm on the sensor or ride-height valve controls the amount of air that enters or exits an air spring. Each chassis has a specified ride height, measured between a given location on the suspension and a point on the chassis frame. Air is added when the coach is riding low, and excess air is bled when the motorhome is riding high. Handling can be adversely affected if the coach is not at the correct ride height. In that case, the rod attached to the arm must be adjusted.

Next, have the alignment checked, including camber, caster, and toe-in. Camber is the tilt of a wheel when viewed from the front or rear of a vehicle. Caster is the angle of the steering axis when viewed from the side of the vehicle. Toe is the extent that tires turn inward or outward when viewed from above.

For Type A motorhomes, it’s also important to check the thrust angle, which is an imaginary line drawn perpendicular to the rear axle’s centerline. It compares how the rear wheels are pointed in relation to the direction the coach is traveling. If the rear axle is at an angle, the rear end of the coach will tend to push off to one side. The driver then compensates by turning the steering wheel in the opposite direction. This results in “dog tracking,” with the rear end offset from the front. You might think the thrust axle should be zero so that everything goes in a straight line, but some chassis specs call for a small thrust angle to compensate for the crown in the road.

Thrust angle adjustments are made by shortening or lengthening the control rod on one side of the rear axle with air springs. Make sure your alignment facility is capable of checking thrust angle. And before adjustments are made, check with your chassis manufacturer and verify the alignment specs for your chassis.

While performing a chassis alignment, a conscientious service tech might find loose or worn parts that also contribute to handling problems. But if inflating tires to the correct pressures, adjusting the ride height (for a diesel pusher), and getting an alignment does not solve your handling problems, further investigation will be needed.

Steering Wheel Free Play

When a driver moves the steering wheel back and forth and the vehicle does not respond as it should, there’s too much free play. This problem can be caused by worn joints or loose connections in the steering mechanism. It’s best to allow a professional service center to do the inspections and checks.

Road Wander

Too much free play in the steering can cause a motorhome to veer back and forth, making it difficult for the driver to stay in a lane. But road wander also can occur even when free play in the steering is not an issue.

Type A motorhomes have a fair amount of rear overhang. Excessive weight hanging over the rear axle means the front axle bears minimal weight, resulting in light steering. Shifting cargo from the rear to the front, or even adding weight to the coach, can help keep the front axle more firmly planted. But when changing the weight distribution, be sure not to exceed the rated capacity of either axle.

Coaches with front leaf springs tend to “walk” from side to side. This usually isn’t caused by worn components but instead is related to the springs’ design. Leaf springs have a certain amount of flex in them because of their bushings, as well as the way the shackle bolts are mounted. If your leaf-spring front axle is walking from side to side, front track bars can be added to help mitigate that problem.

Before attempting to correct a front-end issue, make sure you don’t have a “tail wagging the dog” situation.

Tail Wagging The Dog

Many issues that appear to be related to the steering system are not caused by the front end of the coach but by the rear. The tail-wagging-the-dog analogy applies here. As a small dog wags its large tail, the front of the dog wobbles. A motorhome reacts in a similar manner when sideways forces (from passing 18-wheelers, for example) are exerted upon its large rear overhang. It’s hard to stop all that weight once it’s in motion. Move the steering wheel back and forth, and you’ll notice that the motion at the rear of the coach affects the front end by moving it in the opposite direction. The coach tends to pivot on its vertical axis at the center of the rear axle. This is especially prevalent on motorhomes with a shorter wheelbase.

The laws of physics dictate that the front of the motorhome will move in response to lateral forces applied to the rear of the coach, but the factors that most affect handling are the length and weight of the coach, the axle configuration, and the type of suspension, as well as side winds and bow wakes from passing 18-wheelers.

A bow wake, as an 18-wheeler begins passing on the left, forces the rear of the motorhome to the right and the front end in the opposite direction. The motorhome driver, trying to stay in his or her lane, compensates by steering to the right. Moments later, as the semi passes by the front of the motorhome, the bow wake presses against the front of the coach and the driver again compensates by steering in the opposite direction. Generally, this effect is more noticeable on lighter motorhomes, vehicles with shorter wheelbases, and those with leaf-spring suspensions.

As mentioned earlier, leaf springs permit quite a bit of flexibility when controlling lateral movement of the axle. The coach body moves laterally in response to pressure applied to the rear of the coach. This causes the leaf spring and mounting hardware to flex and allows the coach to move sideways in relation to the axle, which stays in contact with the road. The sideways movement of the coach causes the front end to move in the opposite direction, requiring steering corrections by the driver. To prevent lateral movement of the coach body in relationship to the rear axle, a Panhard rod, commonly referred to as a track bar, can be added.

A track bar is a long steel rod with attachment points at each end of either a rear axle or a solid I-beam front axle. One end of the rod mounts to a bracket on the coach frame on one side of the coach; the other end mounts to a bracket on the rear axle at the other side of the coach. This ties the coach body and axle together laterally so that the axle cannot walk out from under the coach. As the motorhome travels over bumps and dips, the track bar pivots to allow unimpeded vertical movement of the coach body. Aftermarket suppliers offer track bars for specific Type A and Type C chassis equipped with leaf springs. Note that diesel pushers with air springs are already equipped with track bars, because the air bags have no ability to locate the axle beneath the coach.

Sway

Sway is the roll or lean of a motorhome in response to pressure exerted from the side. When driving through a curve, the top of a motorhome tends to lean to the outside of the curve, compressing the outside springs and decompressing those on the inside. Sway also can occur when a motorhome encounters heavy wind gusts or when it pulls onto a driveway ramp that pitches the coach from side to side.

An anti-sway bar (also referred to as a sway bar) strengthens the suspension system. Generally, the horseshoe-shaped steel bar is attached to the middle of the axle, and each end of the bar is secured to the chassis frame rails via mounting hardware. The horseshoe wants to remain flat, so when energy is applied to the left side of the coach, the left side of the anti-sway bar wants to twist upward, while the right side wants to twist downward. The anti-sway bar attempts to flatten itself out, returning the coach to a level position.

Anti-sway bars are available in various diameters and corresponding strengths. The bar should be sized for a particular vehicle. The heavier the vehicle, the larger the diameter of the bar. But if an anti-sway bar is too heavy, weight (and traction) will be removed from the inner wheel as a vehicle rounds a curve. On the other hand, a bar that allows excessive sway is not desirable, either. On an older, well-traveled motorhome, the anti-sway bar may have weakened and be in need of replacement. In addition, an anti-sway bar’s end link bushings can wear out, allowing free play in the linkage. In that case, the suspension must move enough to take up the play before the anti-sway bar can be effective.

On a motorhome with air springs, motion control units (MCUs) can be added to assist in managing sway. MCUs — compact cylinders that connect in the air line to each air bag — control the flow rate in and out of the bag via preset valves. They won’t replace an anti-sway bar but can be a cost-effective means of lessening sway.

Porpoising

A porpoise swims by propelling its body up and down. A vehicle can experience similar oscillating action as first its front axle, and then its rear axle, encounters a bump. Porpoising is more prevalent in motorhomes with shorter wheelbases. A longer distance between the front and rear axles gives the suspension time to settle out between bumps. Often, porpoising can be controlled by changing the shock absorbers, assuming that the springs are in good shape.

Shock absorbers dampen the compression and extension of the suspension to prevent the axle from bouncing up and down indefinitely. Within a shock absorber is a piston that moves inside a hydraulic-fluid-filled tube. As the piston moves, the fluid passes through orifices and valves that restrict the flow, controlling the resistance to suspension movement. The kinetic energy of the suspension movement is converted into heat.

Shock absorbers are velocity-sensitive, so the resistance increases the faster that the suspension moves. Overly stiff shock absorbers deliver a rougher ride, while overly soft shocks allow excessive movement and rebounds, such as in porpoising.

Gas-filled shock absorbers perform better than standard shock absorbers, albeit at a higher price. Shock absorber fluid can foam and aerate with use, but gas-filled shocks minimize this by adding a chamber of high-pressure compressed nitrogen beneath the hydraulic oil, separated by a floating piston to prevent the gas from mixing with the oil. As the damper compresses, the oil is displaced and compresses the gas in the chamber. The gas then expands to its normal volume as the shock extends, ensuring that even the smallest movements are dampened.

Adjustable high-quality shocks, such as those made by Koni, allow the stiffness level to be set when the shock absorber is installed. Many owners install them at full stiffness and never adjust them again. Even so, Koni shocks often yield an improved ride and handling. Koni’s premier shocks feature Frequency Selective Damping technology, which the company describes as “an extra tuning option” designed to improve handling and comfort.

The shock absorber originally installed on your chassis likely was selected because of price, not performance. For improved performance, install a shock absorber with a large-diameter piston. RoadKing is a popular brand among owners of Type A motorhomes. According to RoadKing’s website, its RV shocks feature a piston with 4.2 square inches of surface area, which is 280 percent more than many standard shock absorbers. This is said to result in less internal pressure in the shock during operation, which reduces ride harshness and can add up to 10 times more control force when damping. Standard motorhome shocks typically develop up to 1,800 pounds of maximum force, while RoadKing big-bore shocks develop up to 4,500 pounds of control per wheel.

Rut Tracking

Rut tracking is the tendency of a vehicle to follow grooves in the road. The tires may shift the vehicle to one side of a ridge in the road surface or to a break between two pavement types. The main causes of rut tracking are tires and front axle weight.

The Roadmaster Suspension Solutions anti-sway bar (top) is designed to improve stability and cornering control.

When there is not enough weight on the front axle, the front tires are not firmly planted, which allows them to be pushed off the road quite easily by variations in the pavement. Typically, front-axle weight issues occur on shorter-wheelbase motorhomes or on longer single-rear-axle coaches with motorcycle carriers or high trailer tongue weights. The extra weight hanging behind the rear axle acts as a lever and removes weight from the front.

Generally, the front axle should carry at least half as much weight as the rear axle. This refers to scale weights as measured when the coach is fully loaded, not the axle capacity ratings.

If the front axle is underweight, options may include adding weight to the front of the motorhome; removing weight from the rear; and rearranging cargo so that heavier items are in the front rather than the rear. In any case, never exceed the gross axle weight rating (GAWR) when adding or transferring weight.

Tires are another consideration. Tires designed for heavy trucks have heavy sidewalls, and when installed on an RV, they tend to follow ruts and deliver a harder ride. Tires designed for RVs have softer sidewalls, flex enough to minimize rut tracking, and offer a smoother ride.

Tire pressures also affect rut tracking. If you can safely reduce tire pressures a bit, you will see some improvement. However, be sure you have accurate four-corner weights and never reduce below the minimum recommended pressures for those weights as shown in the tire manufacturer’s inflation tables.

Each of the handling issues we’ve described can be corrected once you’ve nailed down the cause. In some cases, you may be able to remedy the situation yourself, or you may require the expertise of a chassis service and alignment center. Either way, the result will be a motorhome that’s a joy to drive.

More Info

Motorhome Chassis

Ford Motor Company

(800) 392-3673

www.ford.com

Freightliner Custom Chassis Corporation

(800) 385-4357

www.fcccrv.com

Spartan Chassis Inc.

(517) 543-6400

www.spartanchassis.com

Shock Absorbers

Koni North America

(859) 586-4100

www.koni-na.com

RoadKing Shocks

(970) 249-1907

www.roadkingshocks.com

ThyssenKrupp Bilstein of America

(800) 537-1085

www.bilstein.com/us/en/

Suspension Systems/Components

Reyco-Granning

(800) 753-0050

www.reycogranning.com

Roadmaster Inc.

(800) 669-9690

www.roadmasterinc.com

SuperSprings International Inc.

(800) 898-0705

www.supersprings.com

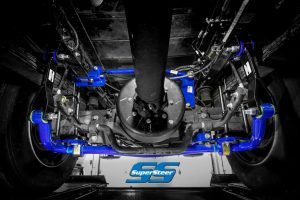

SuperSteer

(888) 898-3281

www.supersteerparts.com