Having a basic understanding of these RV components can assist owners in diagnosing charging issues.

By Steve Froese, F276276

March 2022

This month, I will introduce an important component of most RV electrical systems: the battery isolation solenoid. Even with advanced electronics technology being utilized in modern recreational vehicles, simple mechanical solenoids remain commonplace, although solid-state devices generally control them.

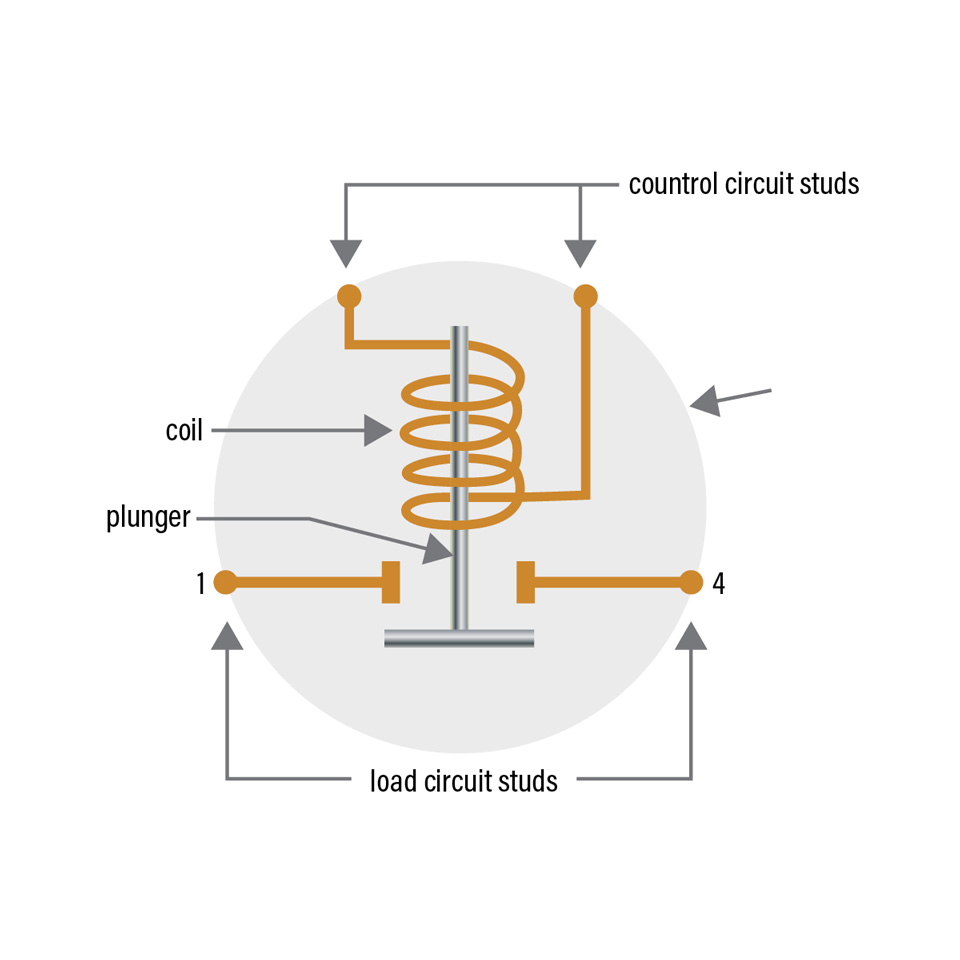

Solenoids are prevalent in motorhomes. They are used to connect or isolate house and chassis battery banks. A solenoid consists of a steel plunger and a coil of wire inside a casing. When current is applied to the coil, the energized coil creates a magnetic field that draws the plunger into it. In basic solenoids, a spring retracts the plunger when the current is removed.

On the outside of the solenoid case are three or four wire terminals. Two of them are large enough to carry very high current. These terminals are electrically connected by the plunger whenever it is drawn into the coil by the magnetic field. One or two smaller terminals on the solenoid allow a reduced current to be applied to energize the coil. Sometimes a second terminal acts as a ground, or the solenoid case itself may serve as a ground. On a 12-volt solenoid, the coil can be energized by as little as approximately 10 volts DC. Travel trailers may rely on a solenoid installed in the towing vehicle for the same purpose: to isolate the towing vehicle starting battery from the trailer batteries.

These solenoids commonly are referred to as battery isolators. When current is applied to the coil, the plunger is pulled into the magnetic field, connecting the two battery terminals and allowing current to flow between them. Since one battery bank is connected to each terminal, an electrical path is created between them. When no current flows through the coil, the plunger is withdrawn by a spring, breaking the continuity between the battery terminals and isolating the battery banks from each other. I should note that lithium batteries involve completely different setups and are outside the scope of this article.

On most newer motorhomes, mechanical solenoids are connected to solid-state controllers that generally are bidirectional. This means that not only are the solenoids closed when the vehicle engine is running but also when shore power or the generator is active. With unidirectional systems, or those with a solenoid connected directly to the ignition signal, running the vehicle engine closes the solenoid and allows the house battery to charge from the alternator; however, plugging into shore power or running the generator does not close the solenoid to allow the chassis battery to charge. Bidirectional systems close the solenoid in both cases, allowing both battery banks to charge whenever the engine is running or when the vehicle is connected to shore power or a generator.

Let’s go into a little more detail on how solid-state battery isolators work. Generally speaking, they take inputs from the ignition, coach battery, and generator (if present) to provide wide control options over battery charging. Properly wired towing vehicles also incorporate battery isolation, although it generally is not bidirectional.

Unlike solenoids alone, solid-state systems monitor the battery voltages and close the solenoid if the voltage of either bank exceeds approximately 12.8 volts (systems may differ in the threshold voltage, depending on manufacturer, model, and type, but 12.8 volts is common).

If the battery voltage exceeds this threshold, it means the battery banks are connected even without shore power or the engine running. The logic is that 12.8 volts would indicate the battery is fully charged, and therefore not at risk of immediate discharge. If the battery is above this voltage, it is likely under a charge condition, which also means the solenoid should be closed. So, the battery state of charge (SOC) for either battery bank will dictate whether the solenoid is open or closed. The controller can determine the SOC from the house battery signal wire input.

The ignition signal wire provides the controller with the SOC of the chassis battery, similarly allowing the controller to determine whether to close the solenoid. As long as the ignition is on (including engine running), the controller is able to hold the solenoid closed, allowing both battery banks to charge. When the ignition is turned off, that input to the controller drops to zero. If the house battery input signal is less than approximately 12.8 volts, the solenoid opens, isolating both batteries. If the house battery voltage is above the threshold voltage, the solenoid remains closed. By this logic, if shore power is connected and charging the house batteries, the controller will detect a voltage higher than 12.8 volts and leave the solenoid closed, allowing the chassis battery to also receive a charge.

Similarly, if the engine is running, the controller will detect a voltage higher than 12.8 volts on the ignition line, thereby closing the solenoid and allowing the house battery to charge from the alternator. If the engine is not running and no shore power or generator input is available, the solenoid will remain closed until the batteries drop below the nominal level, at which time the solenoid will open to protect the chassis battery from discharge.

Finally, if the RV is equipped with an onboard generator, the control unit detects when the generator and engine both are running. In that case, the controller opens the solenoid. This may seem counterintuitive, but it protects the alternator by not allowing back-feed voltage from the generator. In this scenario, the open solenoid allows the alternator to charge the chassis battery bank while the generator (or inverter or converter) charges the house batteries, keeping both systems isolated from each other.

It is not uncommon for battery isolation systems to fail. When a charging system on an RV goes on the fritz, it often is manifested as the house batteries not charging while the engine is running, or the chassis batteries not charging when shore power or a generator is activated. The problem usually involves a failure of the mechanical solenoid, as they tend to stop working after a certain number of cycles. That is why older coaches often experience this issue. It also can be caused by a blown fuse, loose wire, etc. It is uncommon for the solid-state controller to fail.

It’s a good idea to know where RV fuses are located. Multiple fuse boxes for motorhome chassis circuits may exist. It also is important to locate the solenoid itself. It usually will be in the engine bay, near the batteries, or in the electrical bay.

While charging system failures may not be linked to the isolation solenoid, it’s a good place to start, since this is fairly easy to troubleshoot, and the part is inexpensive to replace. I rank solenoid troubleshooting as a 2 out of 5 in difficulty level.

Next month, I’ll cover troubleshooting RV charging systems from an isolation solenoid perspective.